The Four Parts Of Stomach: Fun Facts About Food Bag And Its Functions

The stomach is a muscular organ found on the upper abdomen's left side that performs the important function of digesting food.

The esophagus delivers food to the stomach. When food reaches the end of the esophagus, it passes through a muscle valve known as the lower esophageal sphincter and into the stomach.

The stomach produces acid and enzymes that aid in the digestion of meals. Rugae are muscular tissue ridges that run the length of the stomach.

The stomach muscles flex on a regular basis, churning the food and aiding digestion. The pyloric sphincter is a muscle valve that allows food to flow from the stomach to the small intestine by opening and closing.

After reading about different parts of the stomach, also check facts about the four tastes on tongue and amount of blood in human body pints.

Funny Facts About Our Tummy

While at repose, the stomach can carry around 0.5 lb (0.2 kg) of food and 7 oz (198.4 g) of gastric acid and bile. Because one meal is processed in about four to six hours, the stomach's capacity is critical because it serves as a food storage facility.

With a change in diet and short, frequent meals, it is possible to exist even without a stomach. In a total gastrectomy, the stomach is surgically removed and the esophagus is connected straight to the small intestine.

The lining of the stomach regenerates at regular intervals to keep the stomach acid in check and the pH stable. To defend itself from the corrosive nature of hydrochloric acid, the stomach lining generates some goblet mucus cells.

The stomach is also necessary for the absorption of important vitamins from our diet, such as vitamin B12. The hydrochloric acid in the stomach and the pepsin enzyme in the stomach break down the trapped Vitamin B12 protein, allowing it to be absorbed into the bloodstream.

Some hormones are generated in part by the stomach's epithelial cells. Some hormones regulate gallbladder contractions, while others increase appetite and produce digestive enzymes and stomach acid.

These hormones enter the circulation straight from the stomach and influence the operation of other organs in the digestive system, such as the liver and pancreas, as well as your brain. In the body's immune system, the stomach serves as the first line of defense.

Stomach acid not only digests food but also sterilizes it.

As a result, many germs and food poisons are killed. The gastrointestinal system also features patches of lymphoid defense cells that are sent out when something that might cause infection makes it beyond the stomach, such as a virus or bacterium.

Cows, giraffes, cattle, and deer, for example, have four-chambered stomachs. This stomach morphology assists in the digestion of plant-based meals, which is the most challenging diet to adhere to when compared to other diets.

Animals without stomachs include carp, lungfish, seahorses, and platypuses. Their esophagus is attached directly to their gut, which is where the food goes once it is swallowed. Every two weeks, the mucous layer in the stomach is formed to prevent the stomach and other nearby organs from corroding or being injured by hydrochloric acid.

The stomach's hydrochloric acid is so concentrated and caustic that it dissolves metals. However, with the support of the mucous layer, the stomach stays protected.

Sugary meals digest quickly, but diets heavy in fat and protein take longer to digest. A typical meal takes five to seven hours to digest, but high fiber and protein-rich foods take a bit longer.

The stomach is around 12 in (30.4 cm) long and 6 in (15.2 cm) broad on average, and it is almost the same size for everyone.

The size of the stomach is unaffected by the individual's weight. As a result, both skinny and fat people have the same stomach size.

Facts About The Four Different Parts Of Stomach

Each of the four parts of the stomach has its own set of cells and activities. The sections are as follows:

Where the contents of the esophagus drain into the stomach are the cardiac area, the fundus, which is produced by the stomach’s top curvature, and the body, which is the primary core area.

The contents of the stomach are kept confined by two smooth muscular valves or sphincters. They are the following:

The sphincter separates the esophagus from the heart. The pyloric sphincter, or pyloric aperture, separates the stomach and small intestine.

The stomach is nourished by the hepatic left gastric, right gastric, and right gastroepiploic branches, as well as the lineal, left gastroepiploic, and short gastric branches. They ramify in the submucous coat before reaching the mucous membrane, feeding the muscular coat.

At the base of the stomach tubules, the arteries split into a plexus of small capillaries that ascend upward between the tubules. They merge with one another to produce a plexus of bigger capillaries that surround the tube openings and form hexagonal meshes surrounding the ducts. There are a lot of lymphatics.

They are made up of a superficial and a deep set, and they go along the organ's two curvatures to the lymph glands. The nerves are the terminal branches of the right and left urethras, as well as other organ components, with the former being placed on the organ's back and the latter on its front.

It also receives a large number of sympathetic branches from the celiac plexus.

Facts About Stomach's Function

The stomach's job is to store and macerate food, as well as to start the early stages of digestion. There are members of various mammalian orders with extremely sacculated forestomachs (like some artiodactyls and some primates).

This division is permanent, and it facilitates the digestion of meals. The 'ruminal' sections of the forestomach of ruminants, which are essentially a modification of the esophagus, are extremely permeable to volatile fatty acids generated by microbial breakdown of complex carbohydrates, as well as active salt and chloride absorption.

A non-glandular, stratified squamous part of the stomach next to the fundic or heart mucosa is seen in several mammalian groups, including rats, perissodactyls, and certain artiodactyls. A restricting ridge (margo plicatus) separates the squamous region of the stomach from the glandular stomach, and it functions as a storage organ for ingested material.

The lamina propria of the limiting ridge of rodents may include a variety of inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils).

Facts About Stomach's Cells

Secretory epithelium cells cover the stomach's surface and extend down into gastric pits and glands.

Mucous cells produce an alkaline mucus that protects the epithelium from shear stress and acid attack. Hydrochloric acid is secreted by parietal cells. Pepsin, a proteolytic enzyme, is secreted by chief cells. G cells release the gastrin hormone.

These cell types are distributed differently in different parts of the stomach; for example, parietal cells are plentiful in body glands but almost non-existent in pyloric glands. A gastric pit may be seen invading the mucosa in the micrograph on the right (fundic region of a raccoon stomach).

All of the surface cells, as well as the cells in the pit's neck, have a foamy look; these are mucous cells. The remaining cell types are located further down in the pit and are difficult to detect.

Saliva is produced by salivary glands, which are situated in the mouth. The amount of saliva in your mouth increases when you consume anything. Saliva contains chemicals (enzymes) that help lubricate food and start the chemical digestion of your meal.

Teeth break down large quantities of food into tiny bits. The quantity of surface area accessible for the body's enzymes to operate on rises as a result. Saliva also contains chemicals that help to prevent germ-borne diseases (bacteria).

Your nervous system regulates the quantity of saliva released. A specific amount of saliva is generally secreted on a regular basis. Your salivary glands can be stimulated by the sight, smell, or concept of food.

You should swallow to get food from your mouth to your gullet (esophagus). Food is pushed to the rear of the mouth with the aid of your tongue. The passageways to your lungs then close and you cease breathing for a brief period of time.

The meal is swallowed by your esophagus. To lubricate food, the esophagus secretes mucus. Muscles pull your food down into your stomach.

Between the esophagus and the first section of the small intestine lies the stomach, which is shaped like a J (duodenum). It's roughly the size of a huge sausage when it's empty.

Its primary role is to aid in the digestion of the food you consume. The stomach's other major job is to store food until the rest of the gastrointestinal tract (gut) is ready to receive it. A meal might be consumed quicker than it can be digested by your intestines.

Digestion entails breaking down food into its simplest components. It can then be absorbed into the circulation and distributed throughout the body through the stomach wall. Enzymes are required since chewing alone does not release all of the important nutrients.

The gut wall is made up of multiple layers. Special glands can be found in the inner layers. Enzymes, hormones, acids, and other chemicals are released by these glands.

Gastric juice, the liquid found in the stomach, is formed by these secretions. The outer layers are made up of muscle and other connective tissue.

The muscles in the stomach wall begin to tighten a few minutes after food enters the stomach (contract). This causes mild waves in the contents of the stomach. This aids in the mixing of food and gastric juice.

The stomach then forces little quantities of food (now known as chyme) into the duodenum using its muscles. There are two sphincters in the stomach, one at the bottom and one at the top.

Sphincters are ring-shaped bands of muscles. The control shuts off when they close the aperture. This prevents chyme from entering the duodenum before it is fully digested.

Small quantities of food (now known as chyme) are subsequently pushed into the duodenum by the stomach's muscles. One at the bottom and one at the top of the stomach are called sphincters.

Sphincters are ring-shaped groups of muscles. The control is closed when they close the aperture. This prevents the chyme from entering the duodenum before it is fully digested.

The brain, the neurological system, and numerous hormones secreted in the gut all play a role in food digestion. Even before you start eating, nerves in your brain send messages to your stomach.

As a result, stomach juice is released in preparation for the arrival of meals. Special cells that sense changes in the body (receptors) provide their own signals after food enters the stomach. More gastric juice is released as a result of these signals, as are more muscle contractions.

Different receptors are activated when food enters the duodenum. These receptors give out signals that cause the muscles to slow down and the amount of gastric juice produced by the stomach to decrease. This prevents the duodenum from becoming overwhelmed with chyme.

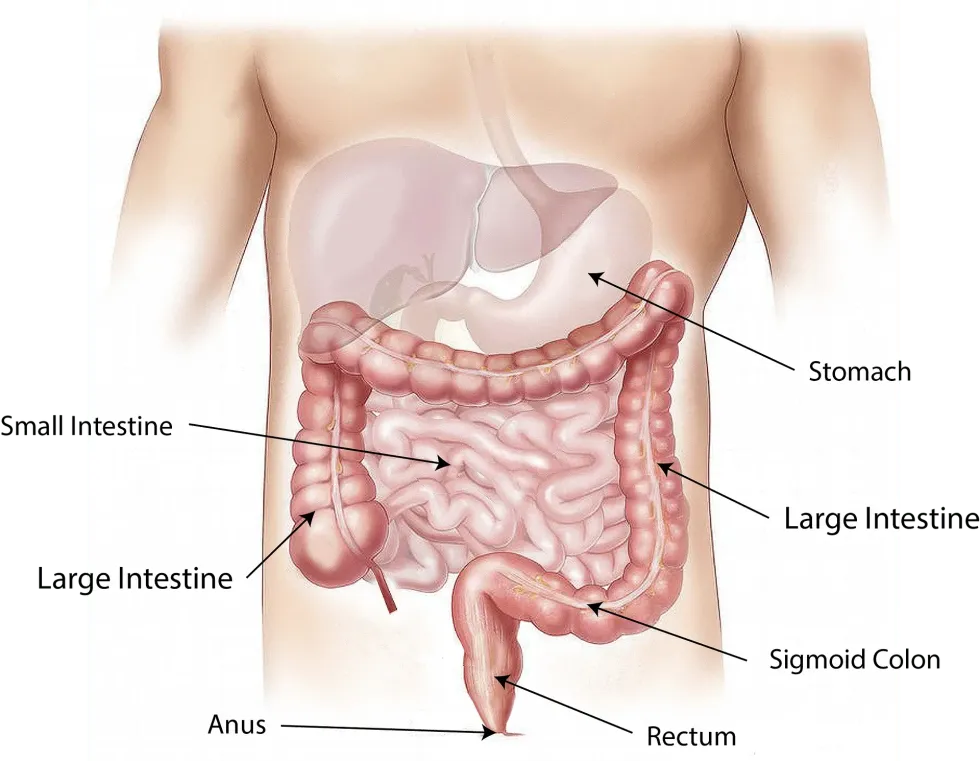

Parts Of The Stomach: We all know that digesting food is an important process in which food passes through the esophagus into our stomach. Many different cells help the digestive system of our body with this process.

The esophagus is full of muscle layers that contract and expand. The food passes through these muscle layers to reach the stomach, as the stomach lies below the esophagus.

The entrance that links the stomach to the esophagus is known as a cardiac orifice. The cardiac orifice is also known as the cardiac region.

In the stomach, many gastric juices contain gastric acid (a high acid produced in the gastric glands), and amino acids mix with the food to help the process of digestion. These gastric juices come from the gastric gland along with other digestive enzymes and gastric secretion from the pyloric canal, gastric tubules, pyloric canal, and fundic glands

At the point where the esophagus meets the stomach, the muscles of the esophagus and diaphragm ordinarily keep the digestive tube sealed. When you swallow, these muscles relax, enabling food to pass through the lower end of the esophagus and into the stomach.

In the event that this mechanism fails, acidic stomach fluids may escape into the esophagus, causing heartburn or irritation.

The upper section of the stomach slides upward towards the diaphragm towards the aperture. This part is known as the fundus. When you swallow, the air that enters your stomach generally fills it up. In the biggest region of the stomach, known as the body, food is churned and broken into minute bits, then combined with acidic chemicals.

Stomach juice (produced by the gastric glands) is composed of digesting enzymes, hydrochloric acid, and other chemicals (such as gastric acid generated by the gastric glands) that are necessary for the absorption of nutrients — around 0.9 gal (4 l) of gastric juice is created every day.

The hydrochloric acid in the gastric juice breaks the meal down, while the digestive juices separate the proteins.

Bacteria are also killed by gastric acid.

'Why do acids not really injure the gut wall?' you might think. The mucus forms a protective layer on the lining of the stomach.

This, together with the bicarbonate, ensures that the hydrochloric acid does not harm the stomach wall. The first section of the stomach below the esophagus is called the cardia. It houses the cardiac sphincter, a small muscular ring that helps prevent stomach contents from refluxing into the esophagus.

The fundus is the circular area below the diaphragm and to the left of the cardia. The stomach's body is the largest and most important portion. This is where the food is combined and begins to decompose.

The lower section of the stomach is known as the antrum. The broken-down food is held in the antrum until it is ready to be released into the small intestine. The pyloric antrum is another name for it.

The region of the stomach that links to the small intestine of our body is known as the pylorus or the pyloric antrum (pyloric sphincter). The pyloric antrum is also known as the pyloric canal or the pyloric sphincter. This pyloric antrum (pyloric canal) functions in a similar way to the stomach entrance.

Here at Kidadl, we have carefully created lots of interesting family-friendly facts for everyone to enjoy! If you liked our suggestions for the four parts of stomach, then why not take a look at anatomy fun facts, or are humans bioluminescent.

We Want Your Photos!

More for You

See All

Bachelors in Business Administration

Aashita DhingraBachelors in Business Administration

Based in Lucknow, India, Aashita is a skilled content creator with experience crafting study guides for high school-aged kids. Her education includes a degree in Business Administration from St. Mary's Convent Inter College, which she leverages to bring a unique perspective to her work. Aashita's passion for writing and education is evident in her ability to craft engaging content.

Disclaimer

1) Kidadl is independent and to make our service free to you the reader we are supported by advertising. We hope you love our recommendations for products and services! What we suggest is selected independently by the Kidadl team. If you purchase using the Buy Now button we may earn a small commission. This does not influence our choices. Prices are correct and items are available at the time the article was published but we cannot guarantee that on the time of reading. Please note that Kidadl is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. We also link to other websites, but are not responsible for their content.

2) At Kidadl, we strive to recommend the very best activities and events. We will always aim to give you accurate information at the date of publication - however, information does change, so it’s important you do your own research, double-check and make the decision that is right for your family. We recognise that not all activities and ideas are appropriate for all children and families or in all circumstances. Our recommended activities are based on age but these are a guide. We recommend that these ideas are used as inspiration, that ideas are undertaken with appropriate adult supervision, and that each adult uses their own discretion and knowledge of their children to consider the safety and suitability. Kidadl cannot accept liability for the execution of these ideas, and parental supervision is advised at all times, as safety is paramount. Anyone using the information provided by Kidadl does so at their own risk and we can not accept liability if things go wrong.

3) Because we are an educational resource, we have quotes and facts about a range of historical and modern figures. We do not endorse the actions of or rhetoric of all the people included in these collections, but we think they are important for growing minds to learn about under the guidance of parents or guardians.